The signal of the yield curve globally rests on its force in changing policy views of politicians and central bankers, writes Bob Savage.

Perhaps the most important lesson to learn as a child is how to lose. Failure and the teachable moments from it are essential to progress. Winning similarly requires grace and some sense of duty back to the game and its players. Have markets and politicians learned these lessons?

The weekend left many wondering if the inverted yield curve as a predicator of trouble was overstated. The big worries about U.S.-China trade talks grind on but the issue over the U.S. political intrigue of the Mueller investigation into Russian meddling into the election came and went with no particular findings against President Trump.Of course, the Russian planes carrying troops to Venezuela maybe a different story and complication to watch. The UK Brexit plans remain in play with Prime Minister May vowing to quit if she wins parliamentary approval for her plan. Winning by losing is in vogue, like owning an equity put, you have to be quick to capture the moment, as was the case in Europe today.

Do yield curve inversions matter?

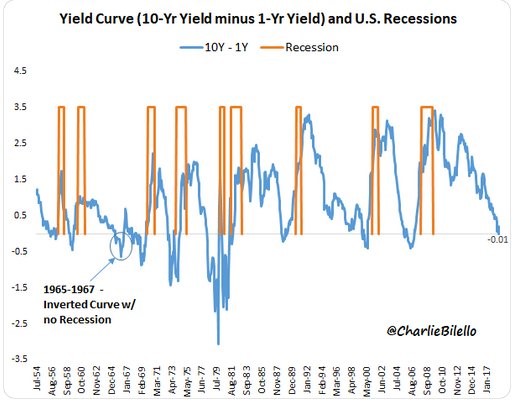

The signal of the yield curve globally rests on its force in changing policy views of politicians and central bankers. The inverted yield curve in the United States remains in play today and it’s going to be the fodder for much of the analyst gloom about 2019. Much of the pressure on global rates is from QE and the zero-interest-rate-policy outside of the United States and so the term-risk premium noise involved in capital flows makes this a less obvious domestic story. There are some other notable points to make about this 2019 inversion as they are not always the predictor of a recession.

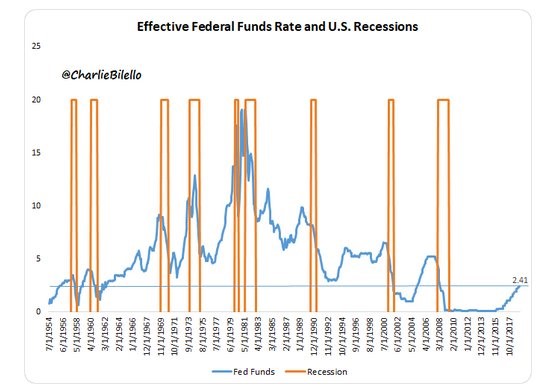

First the Fed Funds rate is lower than any other such inversion with the average over the last 50 years being 6.2% rather than the present 2.4%.

Second the chance for a false signal remains. The last such example was 1965-1967 when the United States also had a notable deficit issue due to the Vietnam War. Also notable is the length of time between an inversion and the actual recession – usually 14 months – making the rest of 2019 more difficult to trade.

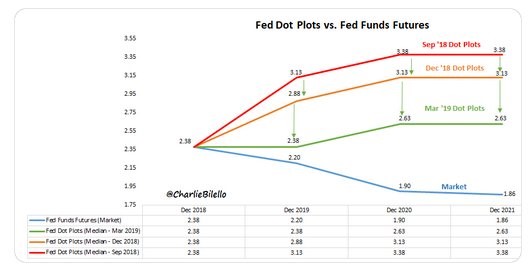

Third the FOMC seems more intent on not starting a slowdown without inflation or any credit bubble, they can ease just as quickly now, as they have learned from previous examples. The Fed doesn’t want to be blamed for killing the economy given the present politics. The problem is that the FOMC still prices in one hike for 2020 while the markets prices in two cuts for 2020. This is where the pain trade lives.