Over the last decade, no matter what’s going on in the broader economy, the the European Central Bank (ECB) has been saying to the market, “We’re confident that inflation will soon reach our goal of 2%.” Don't believe their forecasts, suggests Matt Kerkhoff, money manager and editor of Sigma Point Capital's Market Analysis.

Even when inflation plunged from 1.6% in 2012 to less than 0.75% in late-2014, the ECB’s message was the same — everything’s fine here guys, inflation will soon return to our target levels, so you better go out and buy something.

Can you imagine any other situation in which a team could be so consistently wrong, year after year, and still keep their jobs? Probably not, and the reason is because in this case, being wrong is their job.

Let me rephrase that. The job of the ECB, or any central bank, is to remain optimistic at all times, regardless of the true underlying state of the economy.

Why is this so important? Because of one simple word: confidence. Our economy, and any economy for that matter, runs on confidence. This is because as humans, we’re an ornery bunch and are driven in large part by emotion.

While we like to think that every decision we make is rational and predicated on a unbiased cost-benefit assessment, we’re all making decisions based on a cascade of neurotransmitters that are constantly running through us.

Whether the decision is to have that extra meal out, buy the new car we’ve been thinking about, or take the leap into a new job, how we “feel” at any given moment makes all the difference in the word. We can each picture times in our lives when our answer would be “let’s go!” and others when we aren’t interested in taking even the slightest bit of risk.

It is said that all of economics happens at the margins. You wouldn’t think that having that extra meal out affects the economy, but if all 330 million Americans make the decision to eat out, that’s an awful lot of economic activity. And economic activity is what drives economic growth.

Central bankers and economists (particularly behavioral economists) have long understood the power of confidence, and this is why so-called “forward guidance” has become such an important tool.

Forward guidance is designed entirely to affect confidence, because confidence is perhaps THE most important channel of growth in our economy. When confidence goes, the economy goes with it. So horrible forecasts are to be expected. Our own Fed does it, as does every other central bank in the world.

Can you imagine a situation where the Fed came out and said, “Well, we think the economy’s headed for recession, so you might want to be careful.”

That would literally cause a recession. Spending would freeze immediately, economic activity would stop, and economic growth would slip below zero. No, the job of central banks and politicians is to be optimistic.

This is because confident consumers will spend a little more, save a little less, take on extra risk, and generally engage in more economic transactions. And those economic transactions are what keeps the world a turnin’.

So next time you see a central bank forecast for inflation, growth, etc., take it with a grain of salt. Your psychology is being managed so that you remain a good economic citizen, and don’t stop spending.

Speaking of confidence, it’s worth noting that this is what many of the most commonly watched measures of consumer sentiment are designed to monitor.

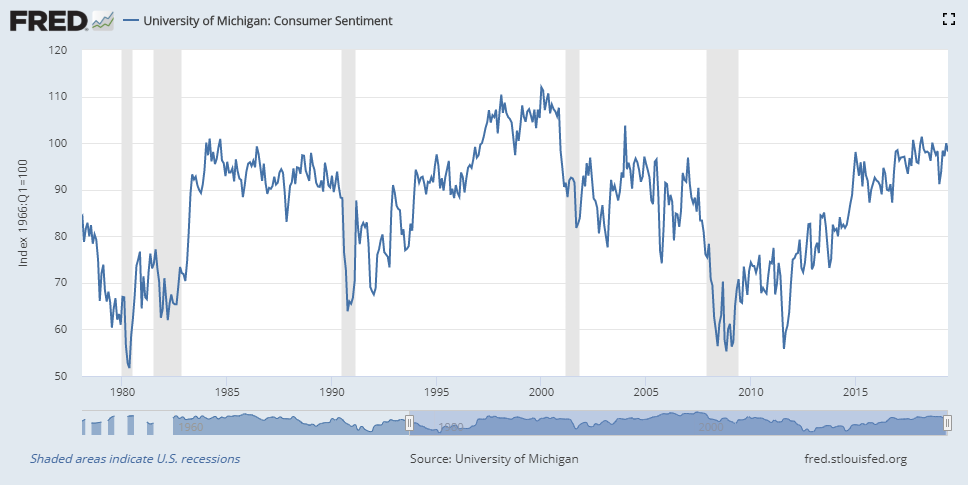

In the chart below, which shows the University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index, we can see that sentiment typically erodes prior to economic recessions. This is to be expected, since that erosion in sentiment leads to a pullback in spending.

Right now consumer confidence, as measured by this index and also The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index, remains elevated, though not at new highs. This is a sign that at least in the short-term, consumer spending should remain buoyant.

Moving on, another way that we can measure confidence is to look at bond spreads. The spread between aggregate junk-rated company debt and Treasuries currently sits at 3.85%, close to the lowest levels this year.

As one would expect, more economically sensitive sectors (such as energy and retail) command higher spreads, as the risk of default is believed to be higher.

All in all, it would seem that confidence at both the consumer and investor level remains relatively undisturbed, despite the trade war, the inverted yield curve, the lack of corporate profit growth, etc. Right now, the same can actually be said for business confidence as well, at least according to the NFIB Small Business Optimism Index.

The last thing I’d like to mention is that confidence can dry up quickly and tends to be correlated with stock prices.

Just like investors have a habit of predicting future inflation based on current levels of inflation, confidence in the future depends on how good things are right now. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, since the stock market itself is a leading indicator.