A stock can only go down by 100%, but there’s no limit to how many times its price can multiply going up. This phenomenon has been on full display with the rise of AI-hardware giant Nvidia Corp. (NVDA). Some are now concerned about NVDA and other big-cap tech names dominating the market. But the general concept of a minority of names driving the bulk of stock market returns is nothing new, writes Sam Ro, editor of TKer.co.

History tells us that the stock market has usually gone up. But that doesn’t mean all stocks go up. Far from it.

In 2017, Arizona State University professor Hendrik Bessembinder made waves with his research paper that observed most stocks had been pretty crummy investments that underperform Treasury bills. Bessembinder published another paper in 2020 with some updated stats that were similarly dismal.

When you consider Bessembinder’s stats alongside the fact that the market as a whole has historically generated an average of 8%-10% per year, you begin to understand that there’s a tremendous skew in the distribution of returns among individual stocks.

In other words: The market’s average returns are the result of a small handful of stocks generating eye-popping returns that offset the majority of stocks producing market-lagging returns.

In a report published in April 2023, S&P Dow Jones Indices (SPDJI) came to a similar conclusion after looking into the historical performance of the S&P 500. Specifically, they found that only 24% of the stocks in the S&P 500 outperformed the average stock’s return from 2002 to 2022. Over the measurement period, the average return on an S&P 500 stock was 390%, while the median stock rose by just 93%. “In such a market, a manager’s success is dependent on his ownership of a relatively small number of strong performers,” they wrote.

Warren Buffett would agree with that sentiment. His legendary knack for picking stocks for Berkshire Hathaway’s equity portfolio helps explain why the company’s shares have massively outperformed the S&P 500 over the years.

However, returns have not been evenly distributed across Berkshire’s stock holdings. “Over the years, I have made many mistakes,” Buffett explained in his annual letter published in 2023. “Our satisfactory results have been the product of about a dozen truly good decisions — that would be about one every five years.“

At the time, he walked through examples including The Coca-Cola Co. (KO) and American Express Co. (AXP), which multiplied in value many times over while returning massive cash dividends.

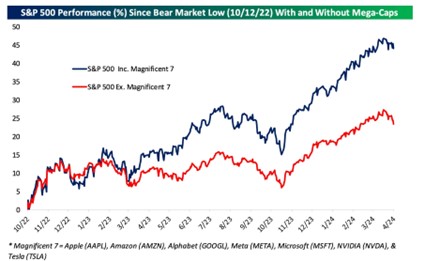

So, is what’s happening today so different from history? The chart below from Bespoke Investment Group shows how the “Magnificent 7” tech names have been responsible for nearly half of the S&P 500’s returns since the beginning of the bull market in October 2022.

The non-Magnificent names haven’t exactly been mediocre. But it’s clear that the strength of a few stocks have mattered. And so I’d argue Bessembinder and Buffett’s insights can be applied to Nvidia and the megacap tech stocks and their effect on broad market returns.

Sure, the concentration of the stock market winners today is unusual in many ways. But the general concept of a minority of names driving the bulk of returns is nothing new. It defines why the broad stock market has climbed for years. And it also explains why Warren Buffett has been so successful.