By themselves, Treasury yields spiking out of control can cause a recession, and October delivered both a 5% yield on 10-year Treasury bonds and 8% fixed-rate mortgages. We have gotten into a situation where the avalanche of Treasury issuance is overwhelming investors. But with all this negative backdrop, the Treasury market is showing signs of exhaustion, counsels Ivan Martchev, investment strategist at Navellier & Associates.

The US Treasury had to issue more debt recently because they could not issue any before the debt ceiling deal, and also because they have to issue more bonds at much higher interest rates to pay the coupons on the ones they had issued already. The situation is starting to look like an out-of-control debt spiral.

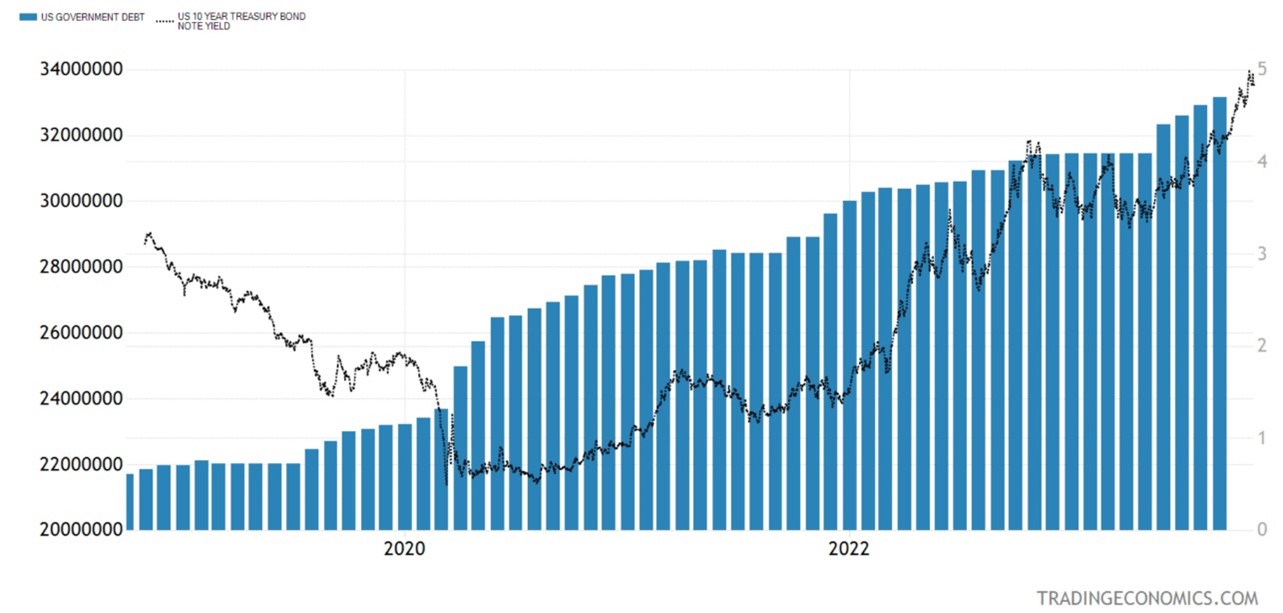

On the chart above, you can see how quickly we went from $22 trillion in Treasury debt (in mid-2019) to over $33 trillion at the end of September 2023.

There were three notable bumps. In 2020, it was COVID spending (necessary to prevent the economy from entering a Second Great Depression). Then it was the Biden Administration’s pet spending projects in 2021 and 2022. Then, the last four rising columns on the right represent the turbo-charged issuance after the debt ceiling deal, coupled with surging interest rates.

As I have stated here before, the deficit situation is not a Republican or Democratic problem, but a deeply entrenched national problem. All four administrations since 2001 ran deficits, but with different excuses. My simple point is that I think we are running out of excuses. Out-of-control spending that was supposed to help the economy recover will end up running it into the ground at a time when interest rates rise at a record pace.

Surging Treasury yields should be self-correcting, in theory; if they rise too fast, they can cause a recession, which by itself will push them lower, along with falling inflation. The reason this has not happened yet is because of the mountains of fixed-rate debt not yet affected by the yield spike.

For example, in the US we have a huge base of fixed-rate mortgages. When interest rates rise, most mortgage payments stay constant. This is not the case in many developed markets in Europe, where a rise in interest rates pushes mortgage payments higher for everyone.

Graphs are for illustrative and discussion purposes only.

As for the Treasury market, an oscillator like the Relative Strength Index is starting to make lower highs, as we are making higher highs in yield, similar to October 2022. All we need is a few weak economic releases or, worst-case, the military situation in Israel to deteriorate, and the 10-year rate could fall closer to 4%, faster than most would anticipate.