A century ago, hyper-inflation was reaching the explosion point in one nation, while a deflationary boom was about to begin in another. The first event caused a national revolution that led the world into its worst nightmare of the century. The second led to another kind of nightmare, but one that helped defeat the first, writes Gary Alexander, senior editor of Navellier & Co.

On October 11, 1923, the German mark – which traded at four per dollar before 1914 – fell to four billion per dollar in the postwar hyper-inflation which destroyed the German currency by the end of November. Retirement savings evaporated, leading to social unrest and the Munich Beer Hall Putsch (a violent insurrection) led by Adolf Hitler and his national socialist (Nazi) Party, with all the horrors that followed.

In America, by contrast, better times were just beginning as the Dow Jones Industrial Index bottomed out at 85.76 on October 27, 1923, marking the effective start of the Roaring 20s bull market, which rocketed up 344% in less than six years, reaching Dow 381 on September 3, 1929 – and that was all a real gain (after inflation), as the 1920s were a mostly deflationary decade, in contrast to bull markets since then.

In the 1920s, America was under the discipline of the gold standard and a relatively enlightened financial management team under the direction of Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. Over in Europe, Germany could have avoided hyper-inflation and returned to its pre-war currency values, were it not for the punitive 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which demanded an unrealistic $33 billion in war reparations.

In America, the Great Depression was not caused by the 1929 stock market crash. The market recovered strongly by the spring of 1930 but was sent into its death spiral by the Smoot-Hawley tariffs in June 1930 and by the Federal Reserve reducing money supply by approximately one-third, as documented by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their “Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960” (1963).

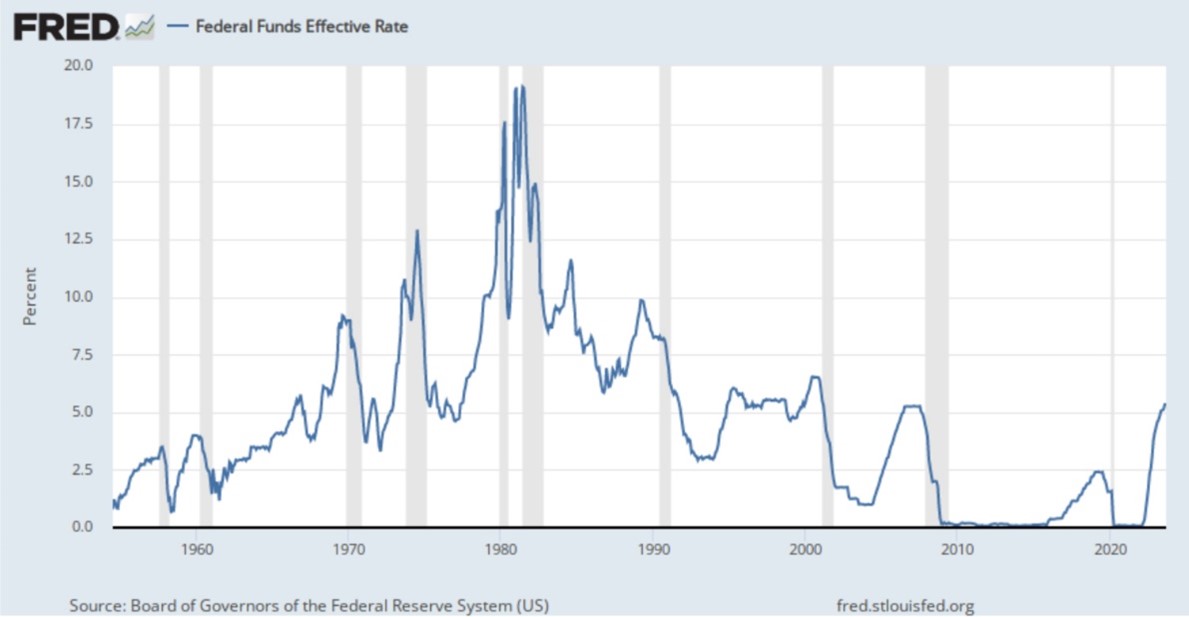

Future Federal Reserve Boards learned from their mistake and avoided deflation in the future, but Paul Volcker (serving 1979-87) sailed close to the shoals of a deflationary shipwreck in 1980-82, after he had been tasked by then-President Jimmy Carter to break the back of inflation. He did so, with a vengeance, probably costing Carter his job, but eventually breaking the back of inflation during Reagan’s presidency.

It’s unlikely that Jerome Powell or any future Federal Reserve Chair will go as far as Paul Volcker did in attacking inflation, since the recent “transitory” inflation surge was not as seriously entrenched as the decade-long stagflation of the 1970s, which preceded Volcker’s blitzkrieg. In fact, this past July brought us deflation in goods sold by manufacturers (-4.1% year-over-year), wholesalers (-5.6%), and retailers (-0.3%), so the Fed has already achieved its desired 2% inflation target, except for the energy sector.

In answering my August 22 query: “Will the 2020s Be a New Roaring 20s, or another Stagflationary 1970s?”, the jury is still out. But the jury also gets to vote – in November 2024, as they did in 1924.

A century ago, the Coolidge team delivered prosperity, while the Hoover team did not. There are many technical reasons why, but Coolidge said it best, “That man [Hoover] has offered me unsolicited advice for six years, all of it bad.”

Coolidge’s biographer Amity Schlaes followed up: “When Hoover’s orders emanated from the Commerce Department, they didn’t matter too much. Come to presidency and the Depression, however, his policies did real damage.” Maybe we need to find “a new Cal” for 2024!