Many investors believed interest rates peaked in late 2022. The optimism about rates (and inflation) was probably wrong, warns Bob Carlson, editor of Retirement Watch.

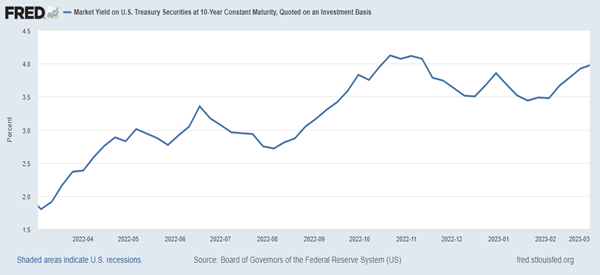

First, a little history: The yield on the 10-year treasury note reached 4.25% in October 2022 and began falling. By late January 2023, the yield was below 3.50%.

Throughout that period, futures market prices indicated investors believed interest rates would decline steadily for the next few years. That interest rate outlook was based on the belief that inflation had peaked and would decline fairly quickly. Declining inflation would cause the Federal Reserve to return to an easy monetary policy by mid-2023.

But a few days ago, the 10-year yield returned to 3.96%. So much for optimism about rates.

More than inflation is keeping interest rates elevated, too. Basic supply and demand factors mean interest rates aren’t likely to return to their 2021 levels, absent a financial crisis.

The Federal Reserve was buying most U.S. government debt during the pandemic period. But the Fed slowed its asset purchases in late 2021. Since then, it has cut the size of its balance sheet by reducing purchases and allowing some bonds and mortgages it holds to mature without replacing them.

At the same time, the federal government’s debt level is increasing. Of course, there are the annual budget deficits. While lower than during the peak pandemic years, the annual deficits still are substantial.

In addition, interest rates are much higher than they were a year ago. As treasury debt matures, the government must issue replacement debt and find new buyers for it, because the Fed no longer is buying all federal debt.

The treasury has to compete with other investments. Cash-like investments now pay yields of around 5%, so the new government debt must pay much higher yields than the older debt. Simply rolling over debt increases federal spending and the deficit because of the higher interest rates that must be paid on the new debt.

This liquidity gap in the markets is likely to keep a floor under interest rates until the Fed is convinced that inflation is headed down to its target rate of 2% and resumes buying most new treasury debt.

Meanwhile, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) Price Index, increased 0.6% in January after rising 0.2% in December. In the past 12 months, the PCE Price Index increased 5.4% as of January, up from 5.3% in December.

The Core PCE Price Index, which excludes food and energy, increased 0.6% in January after rising 0.4% in December. For the past 12 months, the Core PCE Price Index increased 4.7% through January, which is up from 4.6% through December.

Recommended Action: Prepare for higher interest rates.