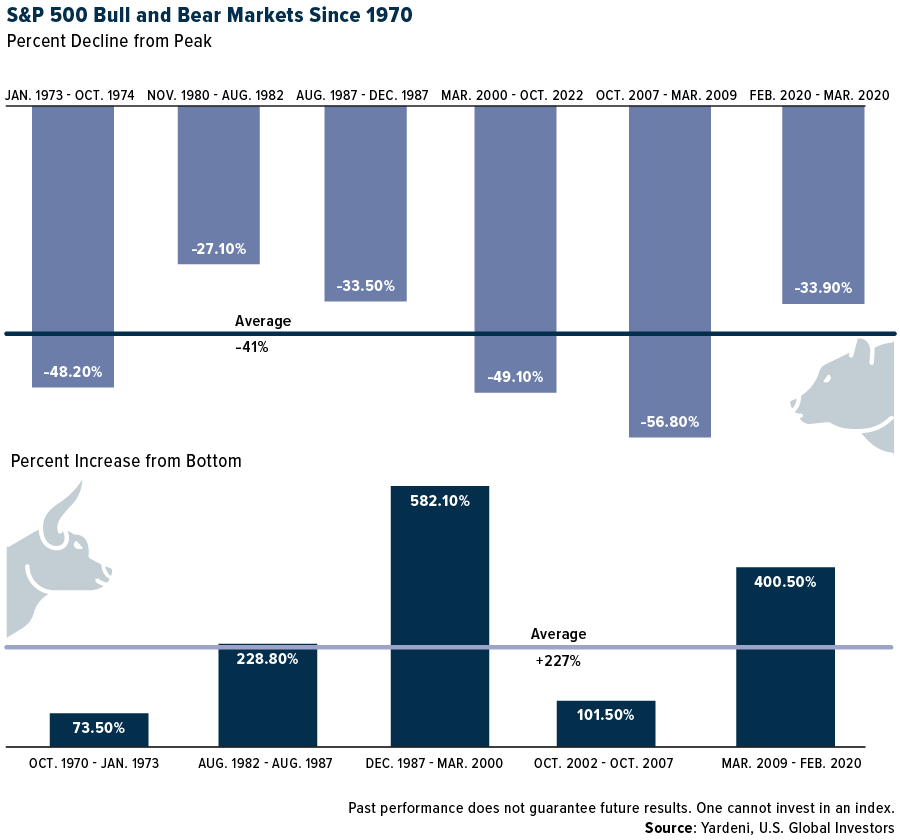

The S&P 500 is off about 20% from its all-time high set in early January, putting stocks in bear market territory. This being the case, I wanted to revisit the historical bull and bear markets from the past 50 years, notes Frank Holmes, CEO of US Global Investors and editor of Investor Alert.

Between 1973 and today, there have been six bear markets, the average decline being 41%. The worst of the five bear markets took place from October 2007 to March 2009 when stocks decreased about 57%.

If this sounds bad, I hope the bull market chart helps brighten your mood. Over the same period, there were five bull markets. Stocks rose 227% on average. The strongest bull market occurred roughly from 1987 to 2000, gaining a phenomenal 582% before crashing due to the dotcom bubble.

What Worked in the 1970s

Inflation continues to hover above an annual rate of 8%, with prices for gasoline, natural gas, food and used vehicles rising the most. The last time inflation was this high, Ronald Reagan was only a year into his first term, and the headline interest rate was around 13%, compared to 1% today.

Forty years ago, the U.S. was experiencing some of the highest inflation in the country’s history after a decade of global oil supply shocks, easy monetary policy and expanding government borrowing. The convertibility of the dollar into gold had recently been suspended, and this had the immediate effect of devaluing the greenback.

There are key differences between then and now—unemployment was alarmingly high in the 1970s and early 80s, for instance—but there are also a few obvious parallels.

Today we’re facing our own global supply chain disruptions, for everything from food to energy, largely as a result of the war in Eastern Europe and ongoing Covid lockdowns. A shortage of semiconductor chips has slowed the manufacture of new automobiles, appliances, data centers and more.

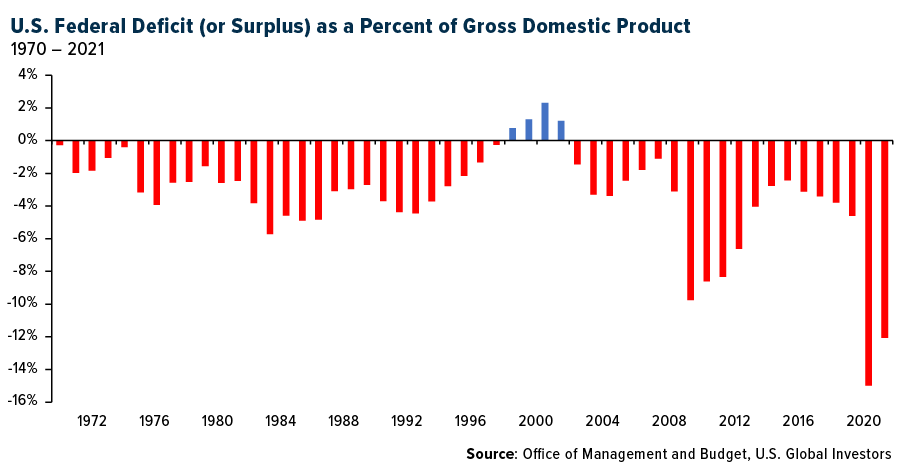

Even though the Federal Reserve has begun raising rates in a new tightening cycle, monetary policy remains extremely accommodative on a historical basis. Combined with trillions of dollars in pandemic-related stimulus, this has served as rocket fuel for corporate borrowing and household debt, both of which stand at all-time highs. For the first time ever, the federal government now owes over $30 trillion, or nearly 130% of the U.S. economy.

The truth is, officials are much more comfortable with large deficits today than they were in the 1970s, and that’s all thanks to modern monetary theory, or MMT. Advocates of MMT believe that deficit spending is perfectly fine since the government can just issue more of its own currency to pay for it all. And thus the cycle continues.

Gold Was the Number One Asset of the 1970s

So what can investors do? Again, history is a valuable guide. The best asset to own in the 1970s was gold, which went from $35 an ounce at the beginning of the decade to as high as $850 by 1980.

Investors sought a hard asset that could go toe-to-toe with inflation and hold its value over time, and the yellow metal fit the bill. Unlike fiat currency, which policymakers can create more of out of thin air, gold requires incredible amounts of time, energy, and money to produce. This helps keep its supply in check.

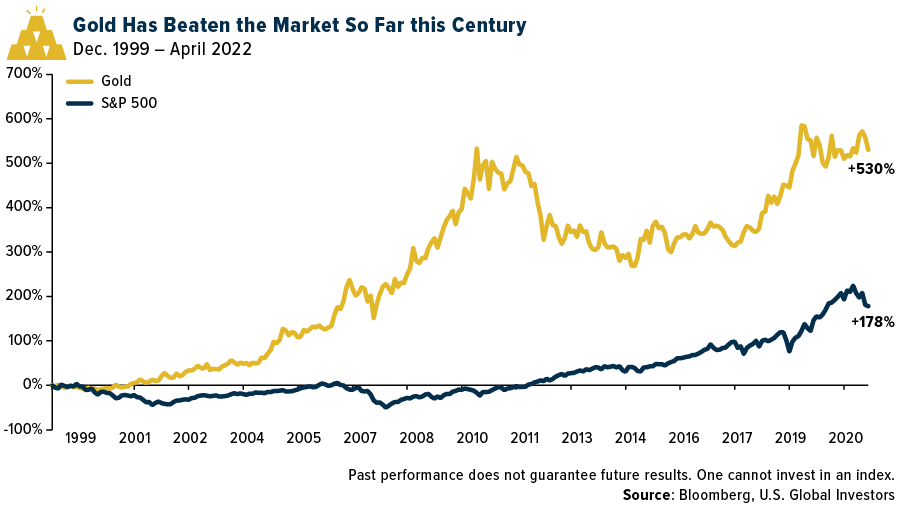

But does the thesis still hold up?

Well, consider this: So far this century, through the end of April 2022, gold has outperformed the S&P 500 by a factor of three. Not bad for a “barbarous relic” that generates no income.

Granted, if we compare gold to the market over the past 10 years, the metal has significantly underperformed as stocks rallied in the longest bull market in history, fueled by low interest rates and low inflation.

That said, the S&P 500 has traded down in 2022 on inflation risk and concerns the Fed will raise borrowing costs much faster than initially anticipated. Gold has been the better asset, then, delivering a positive return in the first four months of the year.

Is Bitcoin Stealing Gold’s Thunder?

Some market watchers may wonder why gold hasn’t climbed even higher. Indeed, when inflation surpassed 8% in March 2022, the metal’s price was not quite able to surpass its record high of $2,073 an ounce, set in August 2020. There’s speculation that the recent popularity of Bitcoin and other digital assets has siphoned off investors’ money that would otherwise have gone to gold.

As a Bitcoin fan myself, I’m not so sure. With a total market cap of $11.5 trillion, gold remains one of the most liquid assets on earth, and unlike Bitcoin, it’s universally respected and traded. Dozens of central banks around the globe continue to hold billions of dollars’ worth of gold in their reserves.

I should also point out that Bitcoin has tumbled dramatically from its all-time high set in November 2021, putting it on a similar path as tech stocks and other risk-on assets. This has made some investors question its perceived role as a store of value, or “digital gold.”

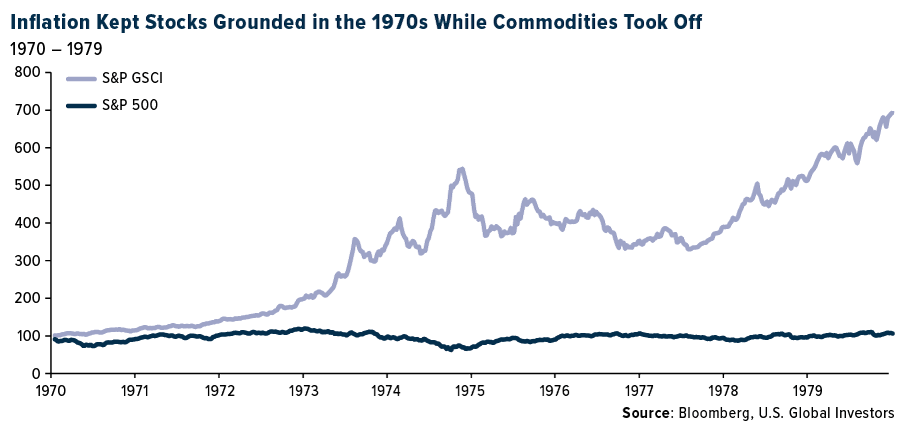

Commodities Were Also a Profitable Bet

Even if physical gold is not hitting new highs, its resilience in the face of runaway inflation tells us that what the market seems to favor right now are hard assets that have intrinsic value. It’s little wonder, then, that prices for nearly every commodity—from metals to energy to agriculture—are going parabolic in many cases.

We saw the same thing happen in the 1970s. The S&P GSCI, which tracks a basket of commodities, surged sevenfold during the decade, while the S&P 500 remained mostly flat.

With commodity prices doing so well right now, we believe energy producers and metal miners look attractive by extension. Many oil and gas companies posted head-turning results in the first quarter of 2022, which was reflected in higher share prices.

London-based Shell, for instance, reported $9.1 billion in profits in Q1, almost three times what it made during the same quarter in 2021. In New York trading, Shell stock rose 23% year-to-date through the end of April.

Inflation may not be as “transitory” as the Fed maintained early on, but at some point, prices will stabilize. Until then, it’s important for investors not to make rash decisions and panic-sell at a loss. If nothing else, it may be prudent simply to hold your positions for a longer duration than you were planning. This isn’t the first spate of inflation we’ve seen, and it likely won’t be the last.